Molecular interactions are fundamental to life as we know it

We build quantitative and predictive understandings of how sequence variation affects macromolecular assembly and function

Recent genome-wide investigations of regulatory elements (e.g., the ENCODE project) suggest that the majority of the genome interacts in some manner with trans-acting factors; a large number of disease-implicated polymorphisms lie not in protein-coding regions but in regulatory regions of DNA that interact directly with DNA-binding factors to regulate gene expression or chromatin structure. These observations underscore the need for a quantitative understanding of sequence-specific affinities for trans-acting factors on DNA. Furthermore, RNA structure and RNA-protein interactions are fundamental to chromatin remodeling, gene expression, alternative splicing, RNA transport, and catalytic activities in the cell. RNA structures at nearly all scales — from short microRNAs to long non-coding RNAs and large assemblies like the ribosome — are implicated in fundamental regulatory roles of basic biological processes that determine phenotypes at the scale of differentiation and pathology. However, because the combinatorial space covered by RNA sequence is astronomical, high-throughput methods for quantitative biochemical investigations of RNA are necessary to build the foundation of our understandings of RNA stability and RNA-protein interactions.

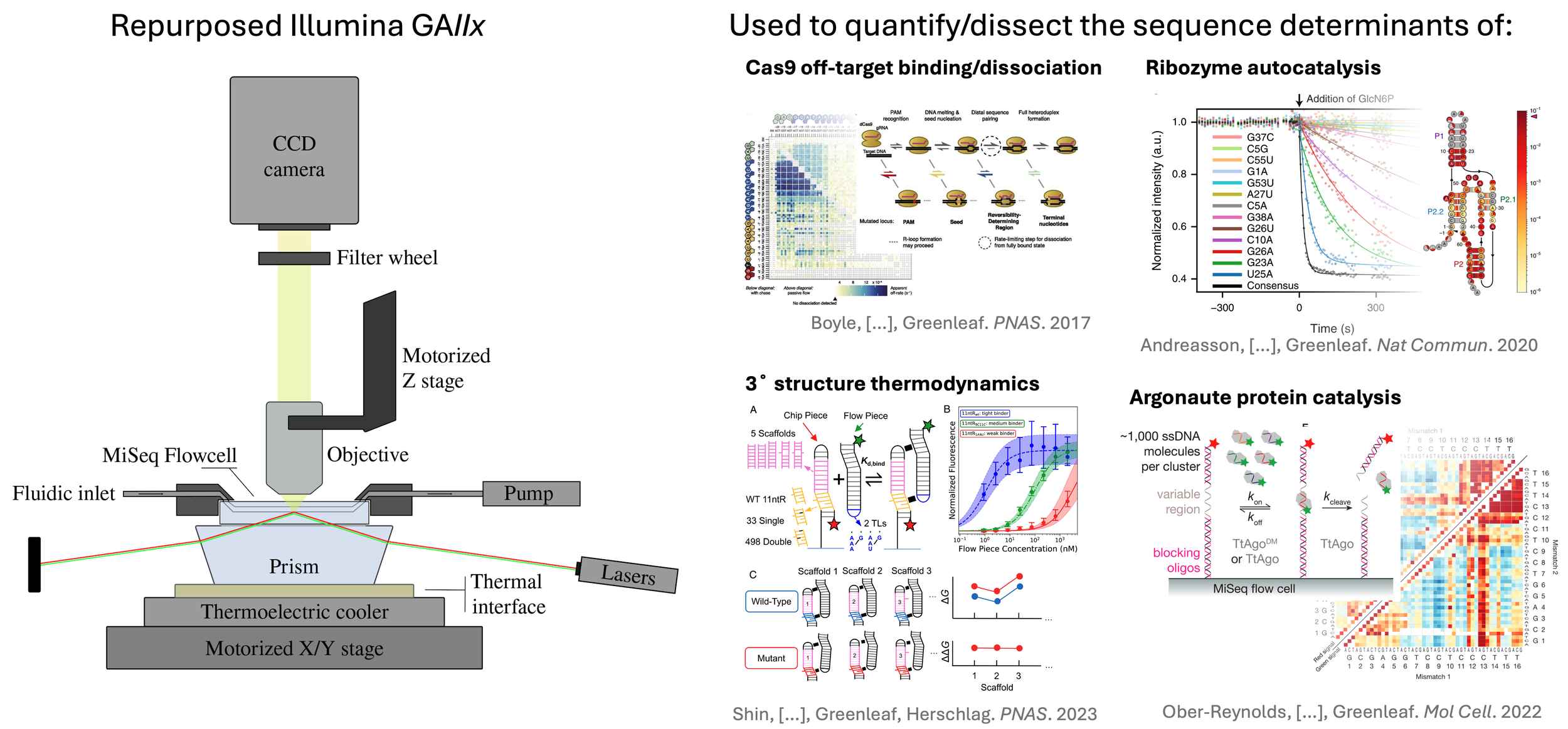

Pioneering work from the Burge lab (MIT) demonstrated the use of a high-throughput sequencing device as a post-hoc DNA array. By extending the sequencing quantitation software, this method quantified the binding affinities of fluorescently-tagged DNA binding proteins to millions of DNA sequences directly on a high-throughput sequencing chip. We have extended this work to bring the underlying technological innovations at the heart of these high-throughput, quantitative measurements of DNA binding proteins, to explore the complex landscapes of DNA-protein, DNA-DNA, RNA-protein, RNA-RNA, and protein-protein interactions. For example, we used E. coli RNA polymerase to synthesize RNAs from previously sequenced DNA clusters on an Illumina high-throughput sequencing flow cell. The DNA was transcribed such that the synthesized RNA remained physically associated with the template, thereby generating a massive diversity of known RNA sequences directly on a high-throughput sequencing instrument. This platform allows the creation of an array of up to ~10^8 unique RNA features, and parallel measurements of binding of fluorescently labeled RNA binding proteins to all these structures. By equilibrating increasing concentrations of RBP with the RNA array, we can construct a binding curve for each sequence, enabling quantification of binding energetics on a massive scale. By generating quantitative energetic maps of intermolecular interactions and intramolecular stabilities over millions of sequence variants, we are contributing unique and powerful datasets for understanding the constraints and requirements for high affinity molecular interactions and catalytic activities.

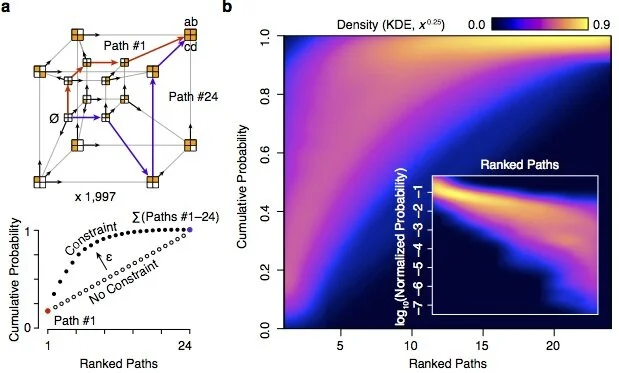

We are interested in uncovering the biophysical basis and evolutionary consequences of sequence-function relationships — linking the biophysical functional landscape to fitness

Using comprehensive biophysical datasets, we are able to reconstruct quantitative evolutionary functional landscapes that relate underlying DNA sequence changes to functional defects or improvements in encoded molecules. This mapping provides a detailed understanding of the biophysical constraints that molecular evolution operates upon, allowing a linkage between quantitative biochemical aspects of biological systems and evolutionary fitness.

High-Throughput, Single-Molecule Biochemistry

Rare or short-lived molecular conformations are often hidden in “bulk” biochemical methods because the heterogeneous states of these biopolymers, which are often of significant interest for building accurate physical understandings biological mechanisms, are lost in the ensemble nature of such experiments. Single-molecule fluorescence methods have lifted the veil of the ensemble average, allowing direct observation of rare and stochastic biomolecular states, affording substantial mechanistic insight into foundational biological processes. Arguably, nowhere has the impact of single-molecule methods been more acutely felt than in understanding the rich diversity of DNA and RNA structural dynamics. However, single-molecule methods are currently extremely cumbersome to apply to large numbers of diverse molecules, making systematic, large-scale investigations of different molecular configurations impossible. In short, the high-throughput revolution in biosciences has left single-molecule biophysics behind. We are working to eliminate this bottleneck, brining single-molecule investigations into the realm of high-throughput biological investigation.