Accessible DNA

Physical accessibility defines the “active” genome

The cell faces a spectacular topological challenge in packing meters of chromosomal DNA inside a ~5 micron nucleus. The cell's solution to this challenge is the hierarchical folding of genomic DNA into regulated structures, the most basic and important of which is the nucleosome. Only a small fraction of the 6 billion DNA bases comprising the human genome are accessible to the machinery of transcription within each cell, while the remainder is compacted and sequestered away by hierarchical folding of DNA into compacted chromatin. Because these changes in chromatin structure require the concerted actions of a host of specialized complexes, the specifics of this physical accessibility encode a durable physical memory of biological state, defining the regulatory landscape of the cell.

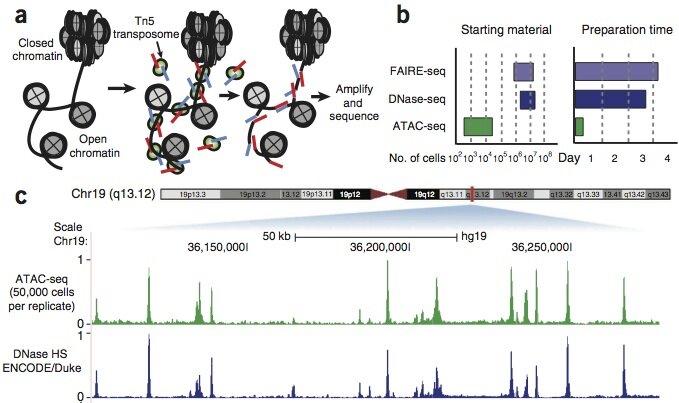

Major insights into this regulatory landscape have come from genome-wide methods such as MNase-seq, ChIP-seq, and DNase-seq, allowing identification of positions of transcription factor (TF) binding, active transcription start sites, nucleosomes and nucleosome modifications, enhancers, and insulators in a wide variety of cell lines and tissue samples. However, current methods for assaying chromatin accessibility, nucleosome positions, TF occupancy, or higher-order annotations of biological "state" of chromatin generally require multiple assays and tens or hundreds of millions of cells as input material, averaging out heterogeneity in cellular populations. These large sample requirements have precluded analysis of the chromatin regulatory landscape of rare phenotypically homogenous cellular sub-types.

ATAC-seq allows rapid, sensitive, and integrative “regulomic” analysis

To address these problems, we have developed integrative, multidimensional epigenomic assays that rely on in vitro transposition of sequencing tags into areas of accessible chromatin. The most widely used such technology that we developed, assay of transposase accessible chromatin (ATAC-seq), rapidly generates multimodal data defining the regulatory landscape of chromatin using as few as ~500 cells — 3-5 orders of magnitude less than other methods. The ATAC-seq assay allows simultaneous, genome-wide information on the positions of 1) open chromatin, 2) transcription factor binding, 3) nucleosomes in regulatory regions, and 4) information on chromatin state annotation.

Beyond Ensemble Measurements; Toward Single-cell “Regulomics”

Ensemble methods of measuring the genomic characteristics of a population “average out” large-scale cell-to-cell heterogeneities, and "drown out" rare variation within the population. As a simple analogy of this problem, let us consider water-based shipping routes from the East Coast to the West Coast of the US. Some of these routes maneuver through the Panama Canal, while another fraction navigate the Straits of Magellan and a few foolhardy captains attempt the Northwest Passage. However the ensemble average of these paths travels through the heart of Brazil, and is a path not taken by any boat - in fact this path is impossible! Almost all of our understandings of large-scale cellular epigenomics are built upon such ensemble-averaged measurements. We are pushing the field to seek information beyond the ensemble and toward single-cell and single-molecule resolution of “regulomic” state using our ATAC-seq and other methods.

How does the genome fold in vivo at the kilobase length-scale?

New methods based on high-throughput sequencing have begun to reveal the genome-wide architecture of chromosomes at the level of single nucleosomes and at the much larger scale of megabase-sized chromosome loops. Between those two size regimes lies chromatin structure on the scale of several nucleosomes, which plays an important role in regulating processes that are essential to normal cell function and development: transcription, DNA replication, and DNA repair. A significant gap remains in our understanding of this level of chromatin organization spanning tens of nucleosomes and a few kilobases of DNA, which we call the secondary structure of chromatin. Decades of work on chromatin's secondary structure has provided conflicting evidence regarding the presence of a “30-nm fiber,” a compacted fiber-like structure comprising an organizational level just above the “beads-on-a-string” of individual nucleosomes. The specific topology of this structure – or indeed the very existence of 30-nm structure in vivo – is still hotly debated, and almost nothing is known about the variability of these putative structures as a function of genome position. We are working to develop a clearer picture of this scale of chromatin organization by integrating both the physical and biochemical views of the nucleus. This work will impact diverse questions such as the regulation of gene expression during normal human development and differentiation, the emergence of cancer and aneuploidy, and the mechanisms of epigenome regulation and maintenance.